Lodges of GaribaldiLodges of Garibaldi

Hearing the name Alpine Lodge, many people may assume it refers to a lodge located in the alpine or in the neighbourhood of Alpine Meadows. Alpine Lodge, however, is actually one of the three lodges we have information about that were located around the Garibaldi Townsite.

The Garibaldi Townsite and several other small communities formed in the Cheakamus Valley near Daisy Lake around the Garibaldi Station of the PGE Railway that opened in 1914. Much of the information the museum has on the area has been provided by Betty Forbes who, along with Ian Barnet, gathered interviews and other documents to put together what Betty called “a record of the history for generations to come.”

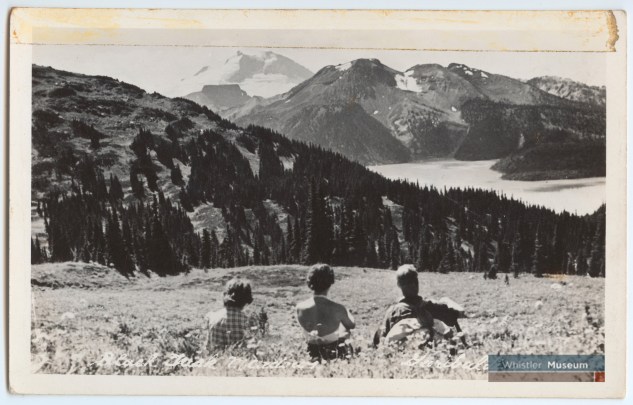

The first lodge, Garibaldi Lodge, was built by Tom Nye in 1014 on the east side of the Cheakamus River. Like Rainbow Lodge, it included a post office and a store. The lodge was operated by Tom Nye and his family until the late 1930s. Garibaldi Lodge was largely inactive during the Second World War until it was reopened by Bill Howard and his father in 1946. According to Bill, one of the more popular trips they offered was up to Black Tusk by horseback. As he recalled, “Very few ever hiked it – very few of our guests anyway. It was a 12-mile (9km) trail that used to go way out by old Daisy Lake. It took about four hours on horseback to get to the top.” Often these excursions would be camping trips, with pack horses carrying supplies to stay overnight.

The Howards operated Garibaldi Lodge for only two years before selling to the Walshes in 1946, who later sold the lodge to Pat Crean and Ian Barnbet in 1970. They winterized the lodge to serve the growing number of skiers heading to Whistler Mountain.

Alpine Lodge, further along the Cheakamus River, was built by the Cranes in 1922. A store was later added in 1926 and a post office. Alpine Lodge was operated by members of the Crane family through the 1940s. In 1970 it was bought by Doug and Diane McDonald and, like Garibaldi Lodge, was winterized. Both lodges appear in hotel directories in publications such as Garibaldi’s Whistler News from the 1970s.

A third lodge, Lake Lucille Lodge, did not make it the 1970s. Built by Shorty Knight in 1929 and close to the lake, it was very popular for fishing. The lodge went through various owners before it was bought by BC Electric in 1957 and used as a construction camp during the building of the Daisy Lake Dam. The lodge was burnt down in 1959 after construction of the dam was completed.

Both Garibaldi and Alpine Lodges were still operating in 1980 when the provincial government issued an Order-in-Council declaring Garibaldi Townsite unsafe due to the instability of the Barrier, a naturally formed lava dam retaining the Garibaldi Lake system.

Despite opposition from the residents, the townsite, which had grown considerably by this time, was to be emptied. One of the last community gatherings was held at Alpine Lodge. As Betty Forbes recalled, “The McDonalds at Alpine Lodge opened their whole lobby, kitchen, and dining to the residents of Garibaldi for a pot-luck supper… It was rather lake a wake, but it was a happy wake.”

Garibaldi Lodge was sold to the government in 1982 and most of the structures were destroyed (one cabin was moved to Pinecrest). Alpine Lodge followed the same fate in 1986.

While the museum has transcripts of oral-history interviews and various photos, it is difficult to create a cohesive history of Garibaldi. Recently, however, Victoria Crompton took over the project from Betty Forbes and Ian Barnet and has now published a book, Garibaldi Townsite: Life & Times, for those interested in learning more about the area.